During the war in the Pacifc, an estimated 161,000 American soldiers lost their lives. Japan lost an estimated 2 million soldiers, along with approximately 800,000 civilians—with roughly a quarter of them dying when the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The carnage is worth keeping in mind when viewing the neat and formal imagery of the ceremony that brought an end to the fighting in the Pacific, and thus the second World War.

“World War II formally ended at 9:08 on a Sunday morning, Sept. 2, 1945, in a knot of varicolored uniforms on the slate-gray veranda deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay,” LIFE reported. “When the last signature had been affixed to Japan’s unconditional surrender, Douglas MacArthur declared with the accent of history, `These proceedings are closed.’”

MacArthur was featured on the cover of LIFE in the Sept. 17, 1945 issue, which included coverage of the surrender ceremony. The cover identified him as “Commander of Japan,” a role he assumed during the American occupation. LIFE devoted nine pages to the ceremony, and four more to a story on the ruin left by the atomic bombs, headlined “What Ended the War.”

The ceremony took 23 minutes and was broadcast on television. LIFE’s account, while largely factual, had its undercurrents of sadness—the story noted that General Douglas MacArthur‘s hand trembled as he spoke.

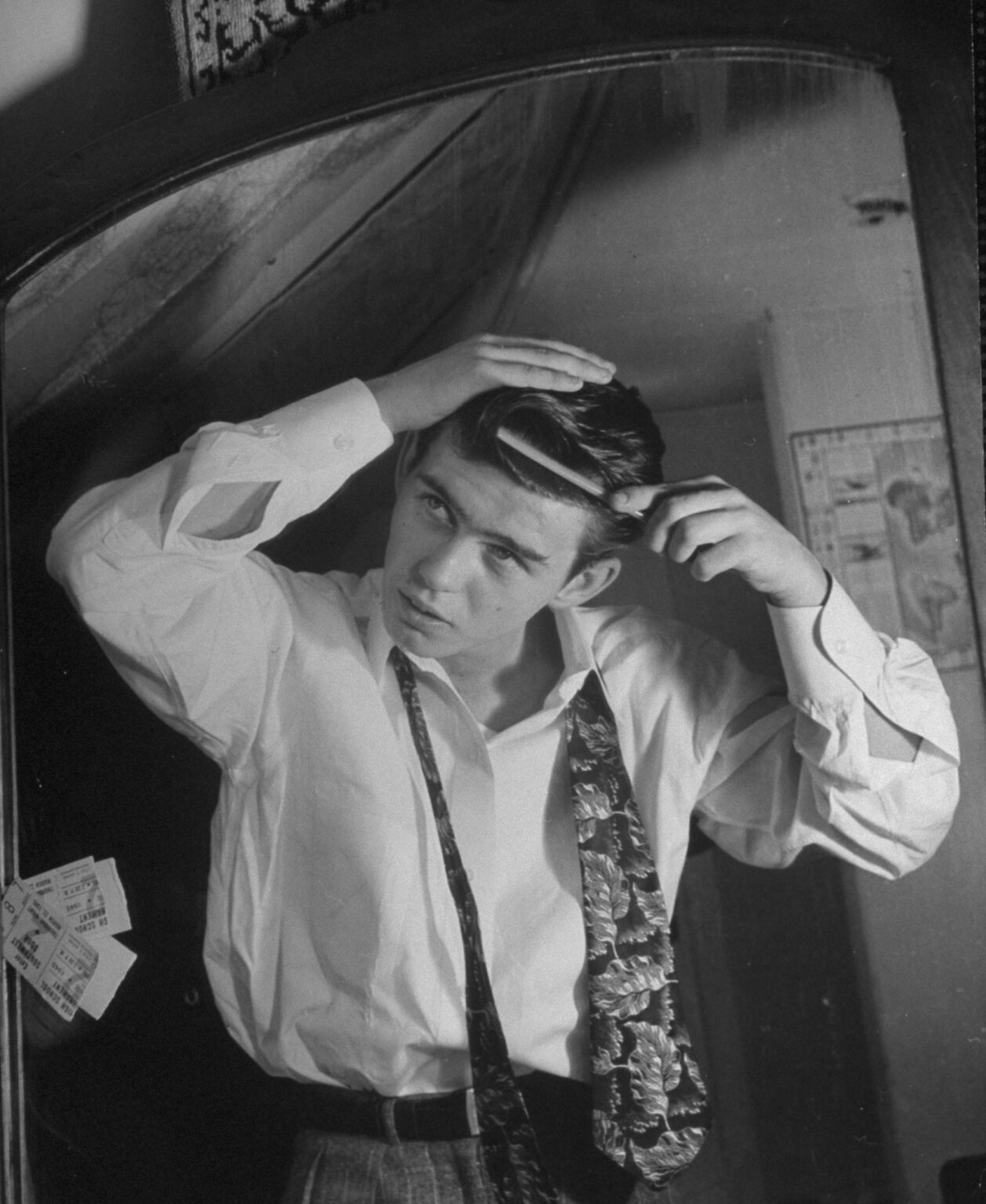

MacArthur had not bothered with a necktie. He read his preliminary remarks sonorously from a sheet of paper. He called on those present to rise above hatred “to that higher dignity which alone benefits the sacred purposes we are about to serve…” He stood stiffly erect, but the hands that held the paper trembled. Then, amid a silence that was almost palpable, the signing began, losers first.

The verbal punch thrown at the end of that paragraph betrayed the bitterness of the four years of fighting, truly a long and brutal journey. It’s fitting that the USS Missouri now resides in Pearl Harbor, available for tours as visitors learn the history of the war in the Pacific.

But on Sept. 2, 1945, everyone signed the documents, a big-boy version of the schoolyard scene in which fighting kids agree to shake hands and go on their way, theoretically having learned something from what their hostilities cost them.

From left to right: an unidentified aide, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Adm. Chester Nimitz and Adm. William F. Bull Halsey arrived on deck for the signing of the official surrender of Japan aboard the USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay, Sept. 2, 1945.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A vessel carrying Japanese envoys pulled up alongside the American battleship USS Missouri for the official signing of the unconditional surrender of Japan held in Tokyo Bay, Japan on Sept. 2, 1945

John Florea/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

The Japanese delegation surrendering in front of Allied officers on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Japan, September 2, 1945.

John Florea/Life PicturesShutterstock

The Japanese delegation awaited the signing of the articles of surrender ending World War II aboard the USS Missouri, Sept. 2, 1945.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Mamoru Shigemitsu (center), Japan’s foreign minister, stood next to his aide, Imperial Army General Yoshijiro Umezu, waiting to sign official surrender documents aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Sept. 2, 1945.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Allied officers and crew crowded the decks of the USS Missouri as senior Japanese delegate Mamoru Shigemitsu signed official surrender documents ending World War II, Sept. 2, 1945.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Soldiers on the USS Missouri watched the signing of the official documents ending World War II, Sept. 2, 1945.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Soldiers on the USS Missouri for the signing of official documents ending World War II, Sept. 2, 1945.

John Florea/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Soldiers aboard the USS Missouri for the signing of the official documents ending World War II, Sept. 2, 1945.

John Florea/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

American officers abd enlisted men saluted during the playing of the US National Anthem prior to the signing of the official surrender of Japan aboard USS Missouri anchored in Tokyo Bay, Sept. 2, 1945.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

The Japanese delegation, including Mamoru Shigemitsu (top hat, cane) and Gen. Yoshijiro Umezu (immediately to the left of Shigemitsu), faced Gen. Douglas MacArthur (at mic) and Allied officers during the official, unconditional surrender of Japan, held aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

J.R. Eyerman/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Gen. Douglas MacArthur signed the official surrender of Japan, as Gen. Jonathan Wainwright and British Gen. Arthur E. Percival looked on aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Sept. 2, 1945.

J.R. Eyerman/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

British Adm. Bruce Fraser signed the official surrender of Japan aboard the USS Missouri, Sept. 2, 1945.

J.R. Eyerman/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Russia’s representative, Gen. Kuzma Derevyanko signed the official surrender of Japan aboard battleship USS Missouri, ending what was for Russia only a 25-day involvement in the Pacific war.

J.R. Eyerman/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

The procession of signatories on the surrender documents including Canadiean Col. L. Moore Musgrave, Sept. 2, 1945.

J.R. Eyerman/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

New Zealand, represented by Vice Marshal Leonard Monk Isitt, was the last of the many signatories of the documents ending World War II during the ceremony on the battleship USS Missouri, Sept. 2, 1945.

J.R. Eyerman/Life Photos/Shutterstock

Japanese signatories looked on as U.S. General Richard Sutherland checked over official documents mistakenly signed in the wrong place by several Allied officers during the surrender of Japan aboard the USS Missouri on Sept. 2, 1945; he fixed the problem with his fountain pen.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock