Written By: Daniel S. Levy

The following is excerpted from the new LIFE special edition Benjamin Franklin: The Patriot Who Changed the World, available at newsstands and online:

On August 27, 1783, a week before he signed the Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution, Benjamin Franklin and his grandson Temple stood with 50,000 Parisians on the Champ de Mars, a large field where the Eiffel Tower now looms. There they watched as the first hydrogen-filled balloon took flight. The rubberized silk sphere soared for 45 minutes and covered 13 miles. When one of the onlookers asked, “What good is it?” Franklin responded, “What purpose does a newborn child have?”

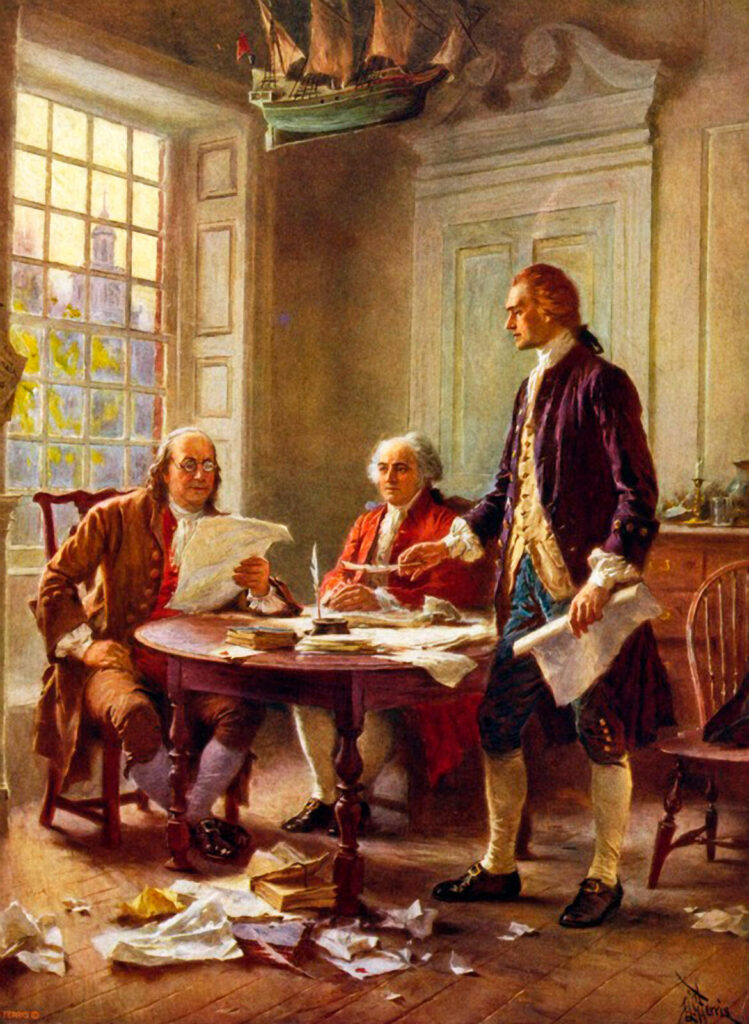

That late summer day, Franklin could not have dreamed of what would become of the newly conceived United States, which had just emerged from seven years of war with Great Britain. Nor could the man whom the early-20th-century historian Frederick Jackson Turner called “the first great American” have imagined as a youth how the trajectory of his life would bring him to the banks of the Seine. In his early years, Franklin was a fervent imperialist, who in 1751 was among the earliest to suggest a united confederation for the British colonies of North America so they could protect themselves from England’s enemies. Yet by 1776 he had renounced his love for king and country; wholly dedicated his life, fortune, and sacred honor to the nascent cause of liberty; and, with Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and others, crafted the Declaration of Independence. Then, needing help for their seemingly quixotic revolt against the world’s most powerful nation, Franklin headed to France, where he used his charm to convince the empire to financially and militarily nurse the infant anti-monarchical country. After negotiating the treaty with England, he accepted the call in 1787 to help redesign America’s federal government and became one of the fathers of the United States Constitution.

Very few Americans did as much as Franklin to make the United States possible. He could envision what others could not, and this made him one of the great minds of the Enlightenment. Even so, he is recalled as the most grandfatherly and folksy of America’s founders, not severe like George Washington, intimidating like Thomas Jefferson, nor prickly like Alexander Hamilton. According to Adams, Franklin “had wit at will. He had humor that when he pleased was delicate and delightful. He had a satire that was good- natured or caustic . . . at his pleasure. He had talents for irony, allegory, and fable that he could adapt with great skill, to the promotion of moral and political truth. He was master of that infantine simplicity which the French call naivete, which never fails to charm.”

The son of an impoverished Boston tallow-candle maker, Franklin started out with minimal advantages. Yet early on he showed sparks of brilliance, clear signs that his was a life of potential. He rejected his parents’ fundamental Puritanism, read religiously, and worshipped what in the 20th century became known as the Protestant work ethic. This made him the proto-embodiment of the Horatio-Alger ethos of social mobility. With just two years of formal education, the teenage Franklin rebelled against the restrictions of his printer’s apprenticeship, fled for Philadelphia, and within a few years became a successful artisan, expertly crafting his hardworking public image so fellow citizens could not help but notice that he was a man worth watching.

But Franklin refused to hog the limelight. America in the early 18th century was a youthful place lacking much of the class restrictions of Europe. Franklin assisted others to get ahead. He not only started groups for Philadelphians like himself who aspired to more, but he imparted advice through his wildly popular Poor Richard’s Almanack, such as that the way to wealth “depends chiefly on two Words, INDUSTRY and FRUGALITY.”

While he packed his almanac with pithy sayings, he also believed in the importance of a free press and an informed public. His brother James had been imprisoned after leaders in Boston took offense at articles in his New-England Courant. So when Franklin bought the Pennsylvania Gazette, he wrote that “Printers are educated in the Belief that when Men differ in Opinion, both Sides ought equally to have the Advantage of being heard by the Publick, and that when Truth and Error have fair Play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter.”

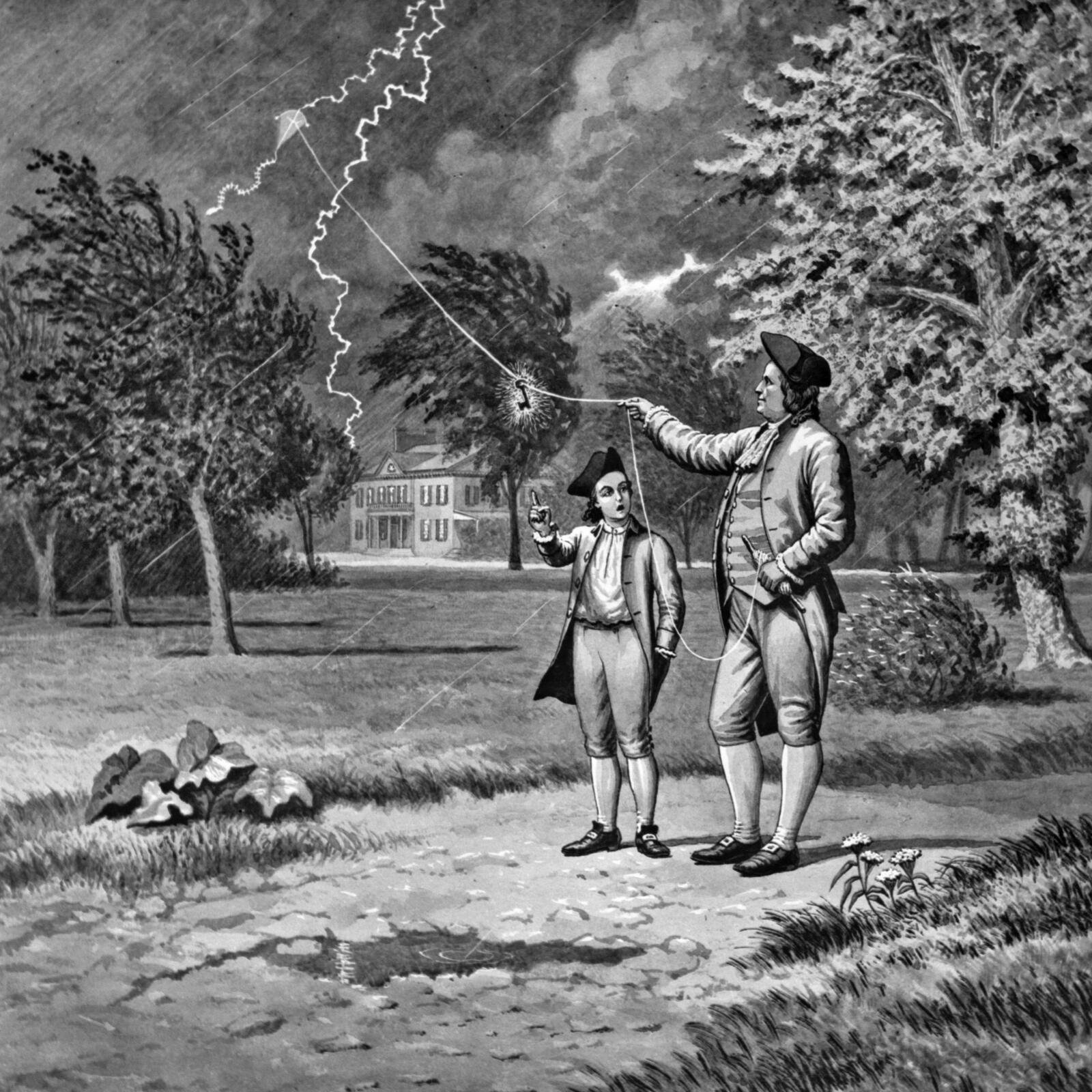

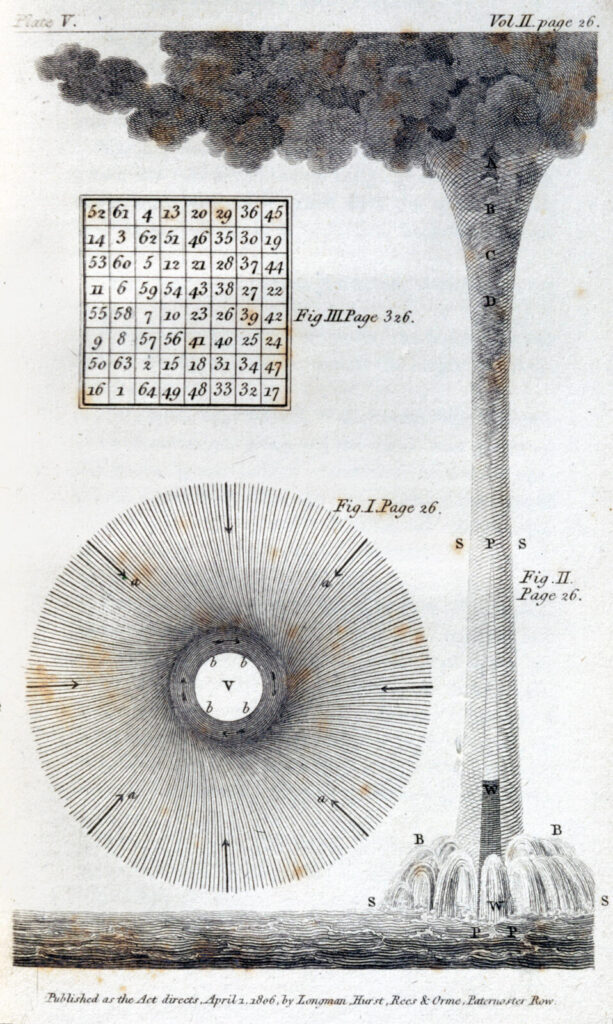

Franklin deeply believed that it was good to do good, and his professional achievements became a means to greater ends. For him, a devotion to public service allowed him to work on the grand level, like the Treaty of Paris, as well as on local issues that impacted his neighbors, such as fire protection and passable city streets. And Franklin’s open mind made him constantly question things. It caused him to wonder about the nature of nature. His observations about lightning sent him out on what seemed the foolhardy hoisting of a kite during a storm and led to a profound understanding of the connection between electricity and lightning. As an inventor-cum-craftsman, he sought practical uses for his discoveries, creating things like lightning rods to protect homes, a better stove to heat frigid colonial houses, and an improved soup bowl for use on wave-tossed ships.

Ultimately, as someone keenly concerned about his own failings—“I was surprised to find myself so much fuller of faults than I had imagined,” he noted in The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin—he sought to correct them. He had once supported enslavement, an institution he would fight against in his twilight years. Even in death, he continued his encouragement of his fellow citizens. The posthumous publication of his autobiography is the most popular accounting of a life, with historian Louis Wright noting how his “homely aphorisms and observations have influenced more Americans than the learned wisdom of all the formal philosophers put together.”

Benjamin Franklin is proof of the American dream, the ability of the common citizen to rise through by-your-bootstraps work, pragmatism, and levelheaded smarts. His example shows that all of us have the potential for greatness.

Here are a selection of images from Benjamin Franklin: The Patriot Who Changed the World:

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Hulton/Getty

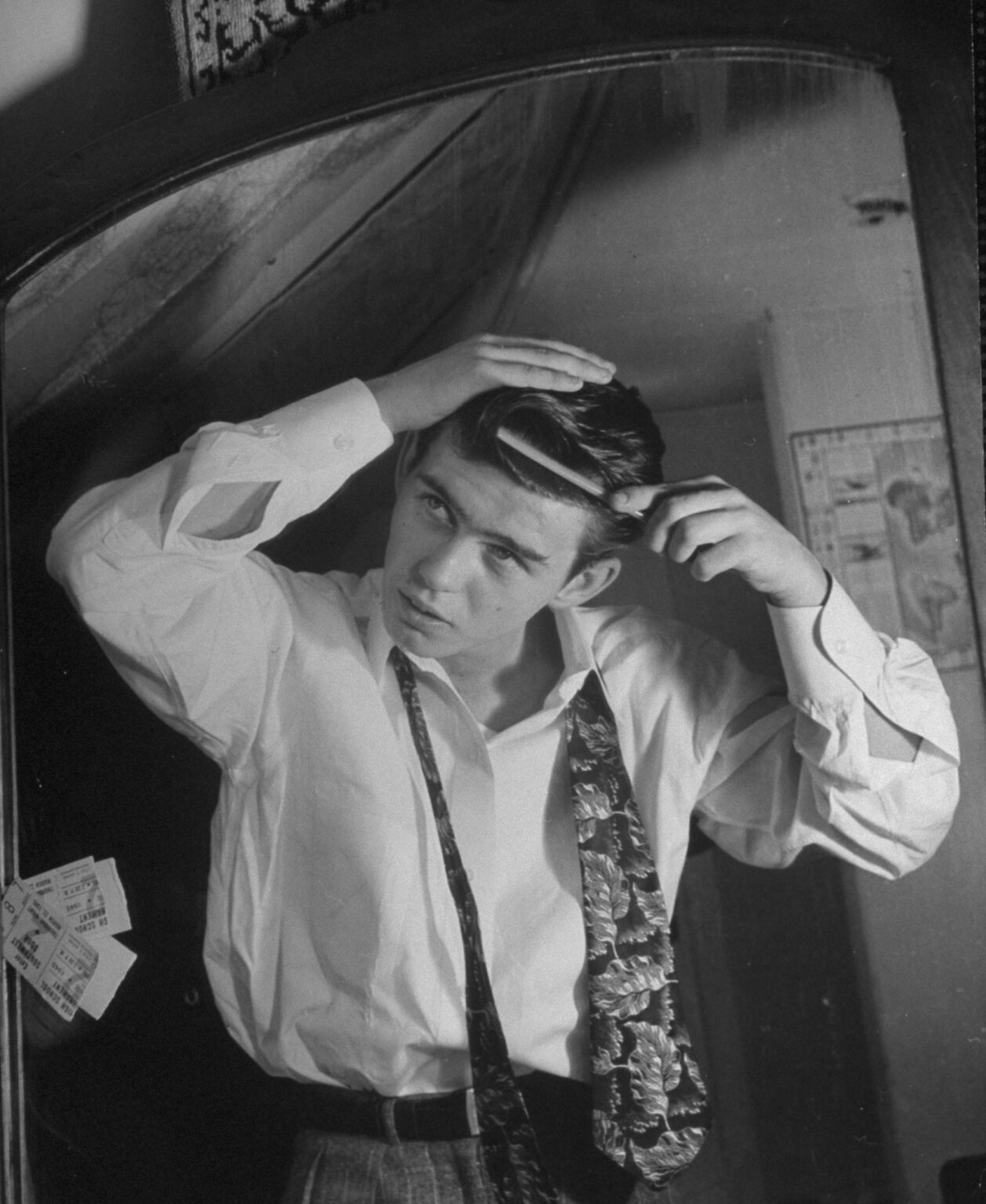

An undated illustration of Benjamin Franklin as a young boy, selling his own ballads.

Bettmann/Getty

An illustration of the structure and appearance of a waterspout, from an article by Benjamin Franklin.

SSPL/Getty

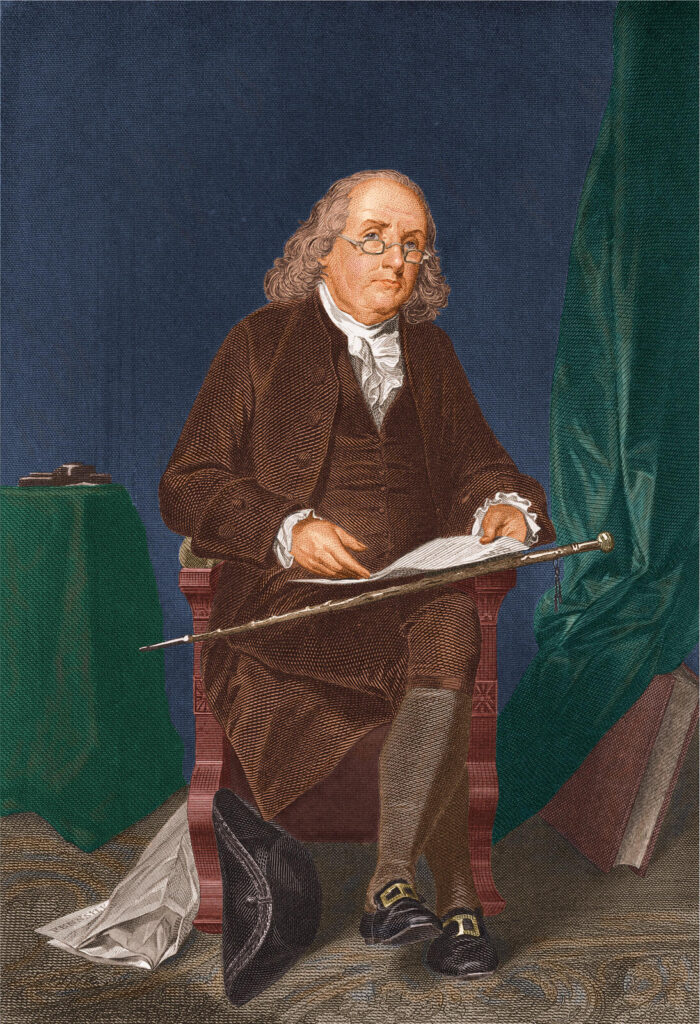

A portrait of Benjamin Franklin from 1767, when he was in London; he had come there ten years earlier to advocate for Pennsylvania, and continued to live there primarily through 1775.

History/Universal Images Group/Getty

Benjamin Franklin (left), with John Adams and Thomas Jefferson during the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, 1776.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty

Ben Franklin, left, at the signing of the U.S. Constitution, 1787.

Henry Hintermeister/Wikimedia

Ben Franklin went to France in 1776 to rally support for America during the Revolutionary War.

Buyenlarge/Archive Photos/Getty

A 1790 illustration of Benjamin Franklin on his deathbed; he died of pleurisy at age 84.

Bettmann/Getty

A portrait of Franklin circa 1770.

Stock Montage/Archive Photos/Getty