Written By: Olivia B. Waxman

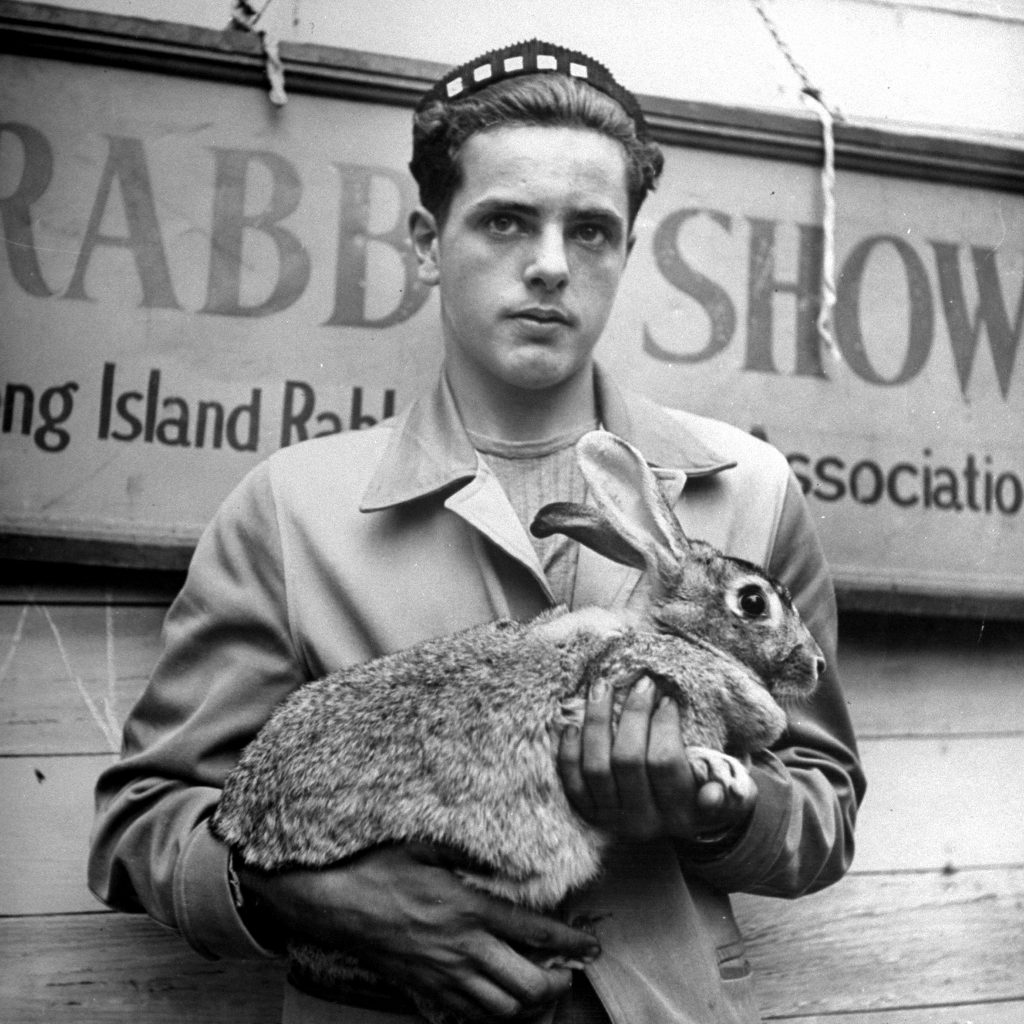

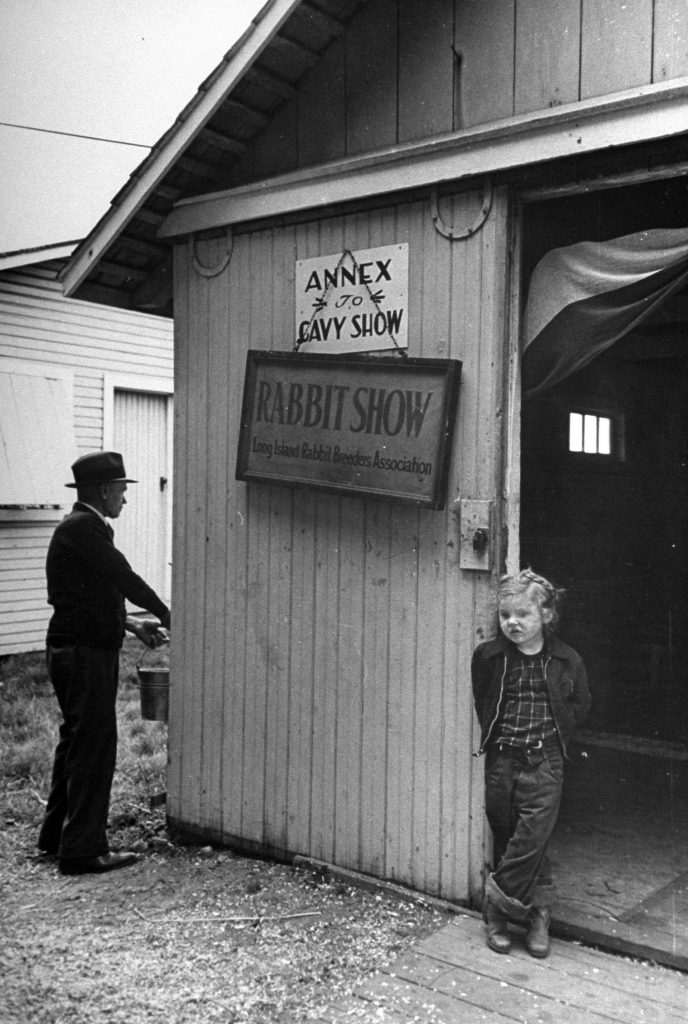

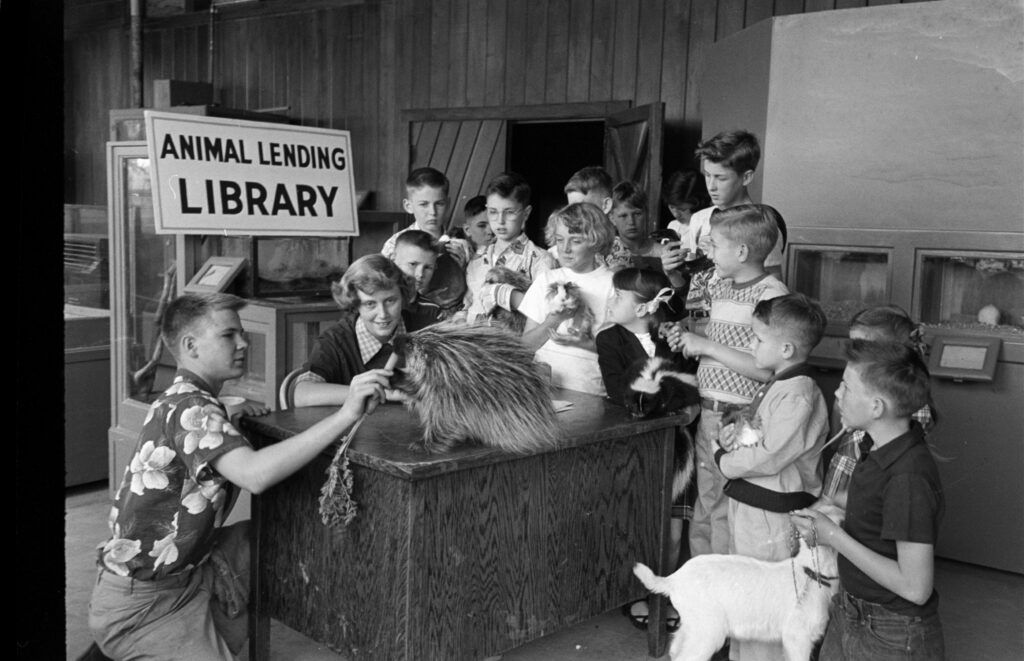

The LIFE photo archives are full of mysteries, great and small—and in this case, furry. At some point around 1943, LIFE sent a photographer to cover a Long Island Rabbit Breeders Association show. There are no contact sheets, no notes or captions were saved, and the photographs were never published. All that can be said is that the event was clearly hopping.

However, while these rabbits seem to have been pampered pets bred for show, one possible reason why rabbit breeding might have been pursued at the time was a lot more practical.

“During the wartime era, when meat was rationed, rabbit breeding was promoted by the USDA as an inexpensive way to raise meat for your own family,” says Margo DeMello, anthropologist and president of the House Rabbit Society, who co-authored Stories Rabbits Tell: A Natural and Cultural History of a Misunderstood Creature. “Many breeders sell them as meat and pets, and that was certainly the case in the ’40s, so these rabbits shows would’ve appealed to both audience.”

The history of cuniculture—the agricultural practice of breeding and raising domestic rabbits—of course goes back much further than that. The Romans kept rabbits in walled gardens known as leporaria. Since rabbit meat was thought to be an aphrodisiac and a fertility aid for women, rabbit breeding was a female-dominated industry. “Men would be responsible for larger animals, and women would be responsible for smaller animals that could be raised at home, closer to the children,” says DeMello, whose nine rabbits reside in their own wing of her home with their own private courtyard outside Albuquerque, N.M. (alongside six chihuahuas, three cats and a parrot).

And, though the WWII push for rabbit consumption might unnerve the Easter bunny, breeding rabbits as food does have Easter-time roots. Catholic monks in southern France are believed to have been some of the first people to domesticate rabbits, and are said to have popularized the practice at their monasteries throughout the Middle Ages, at which point the church apparently considered the ancient delicacy of “laurice” rabbit fetuses or newborns more like fish than animal meat, thus allowing them to be eaten during Lent.

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

1943 Rabbit Show

Marie Hansen The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock